Zone 8B: Polyculture Vegetable Succession Planting

Planning your vegetable garden for maximum productivity as a beginner can feel like you’re drowning in a sea of information. I remember in my first year, sitting down with my bag of seeds and my notebook over the winter, trying to figure out what to plant when and where and feeling very overwhelmed. Not only is it difficult to find information specific to your climate (for us here in Seattle, Zone 8B), there aren’t any real rules when it comes to gardening. There are different methods many people would agree generally work and always new systems to experiment with and adapt to your unique property, budget, time constraints, etc. There is a lot of nuance in working with plants but for those of us just starting out, it can be really helpful to have a guidebook to follow until we are ready to go maverick.

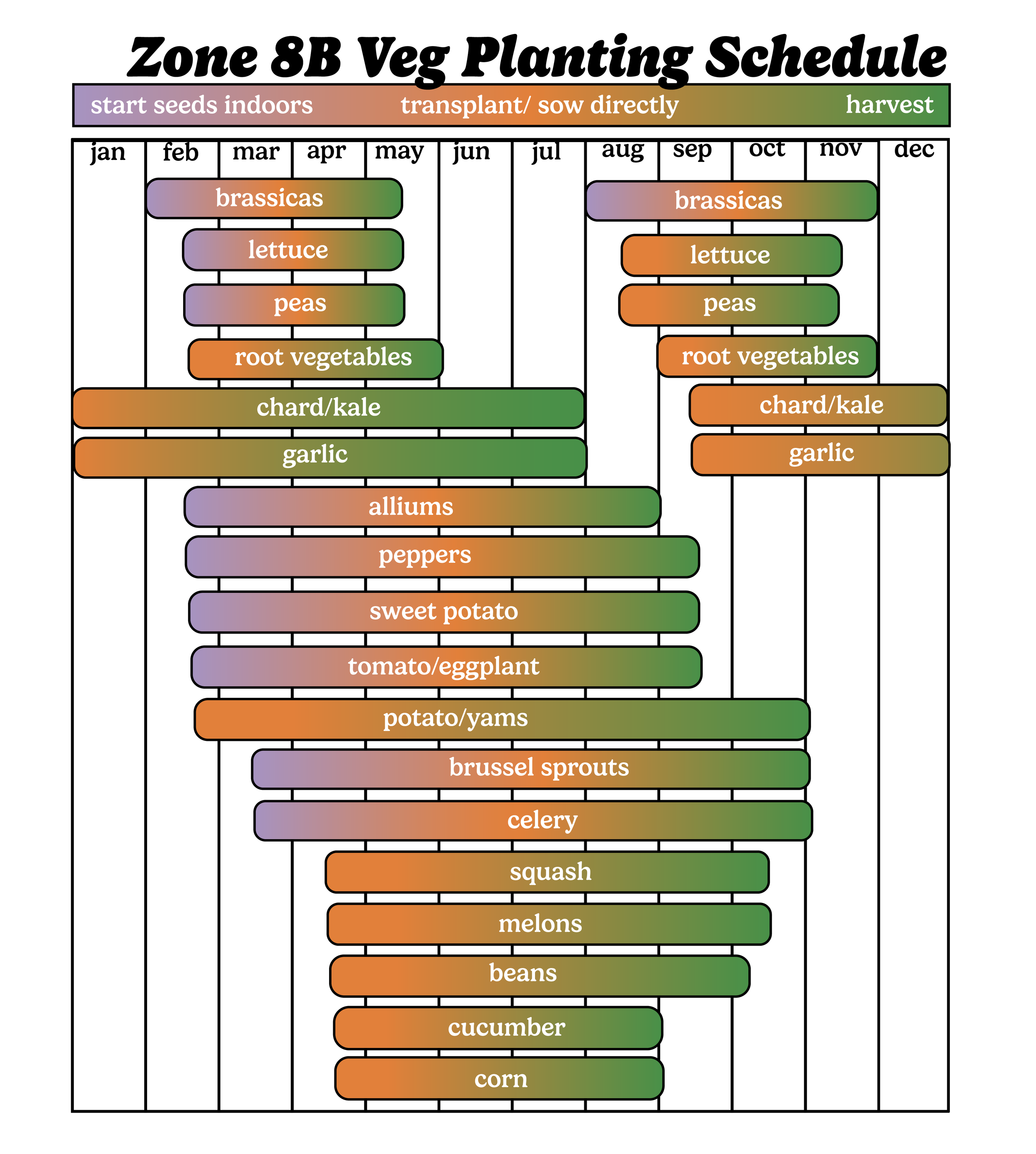

We created these graphics for ourselves to provide a quick visual reference for remembering our methods for building synergistic but simple vegetable polyculture builds and how to succession plant them for maximum garden yields and minimum headache.

Planting Schedule

I think the most important thing to remember when you are trying to wrap your head around the cycles of planting and harvesting is that vegetables in the same family tend to have the same planting schedule. A lot of succession planting charts set out each type of commonly grown vegetable individually but I chose to group them together as much as possible so you can see the bigger picture (the forest through the trees if you will!) and start to wrap your head around the logic and patterns in the growing season rather than getting lost in the details. Let me clarify the exceptions to help you understand the above graphic when planning your garden.

The majority of brassicas such as broccoli, cauliflower, and cabbage like to be started indoors, planted and harvested at the same time in the cold shoulder seasons of spring and fall. Kale and chard are an exception as they like the shoulder seasons but are usually hardy enough to keep producing through the winter as well. Brussel sprouts are also a unique exception because they like to be planted later on so they can be harvested after the first frost which makes them sweeter. Turnips and radishes are also in the brassica family but they act more like carrots and their other root vegetable look alikes than the above ground brassicas.

Most alliums such as onions, leeks, chives and scallions are all typically started indoors and transplanted for spring but garlic specifically doesn’t like to be started indoors and has a longer growing season over the winter.

Root vegetables can come from a variety of plant families but carrots, turnips, beets and radishes all like to be sown directly in the cold shoulder seasons. While celery is in the same family as carrots, their unique growing season is most similar to brussel sprouts, they need to be planted and harvested when there is no risk of frost.

Succession Planting

Our beautifully jam packed garden summer 2022

Succession planting is the practice of keeping garden beds productive year round by planting, harvesting and then planting new plants after them. For plants that can be started indoors, it makes sense to start the next round of seeds indoors timed out so you can plant seedlings with a headstart on growth to replace the plants at the end of their life cycle. For plants that don’t like to be grown indoors and prefer to be sown directly (like squash. garlic, corn and carrots), you simply sow the seed in the space left by the plants you just removed (and hopefully mulched into the soil or added to your compost pile so you can add that organic matter back to the beds!).

Technically every unique variety of plant should have specific information about how many days it takes to germinate, to harvest and when to plant it. The pro way to plan your garden would be to take every single seed packet, calculate the dates for starting indoors, direct sowing and harvesting based on the last frost date in your area and the seed information and make your own master excel sheet or graphic like the first one here for every variety you are planting, finding another plant whose planting date aligns with the harvest date of the one before and succession planting individually. This is an awesome technique but I know that even for myself as an intermediate vegetable gardener that is simply not how I want to spend my time. I would much rather make some generalizations about when plants of different families need to be planted or harvested, whether they like being grown indoors or direct sown, and plan them in groups that will be planted and supplanted at the same time. There’s a reason why the classic Three Sister’s guild of corn, beans and squash is one of the easiest to execute, all three vegetables need to be planted and harvested around the same time. I used this same logic to group together vegetables you can grow together, take out together and replace with another group.

Polyculture Guilds

Contrary to the standard methods of “modern” agriculture, plants do not like to be grown in straight lines or rows or in beds of all the same kind of plants. Wild spaces have taught us that thriving ecosystems (with integrated pest management, weed suppression and pollination built in) are built by plants working together. Different plants fix nitrogen, provide shade, help retain water, attract or deter insects and aid in absorbing nutrients. In general, a polyculture guild is a minimum of three plants grown in the same space (whether that’s one entire bed or a section of a bed) and there really is no maxing out of benefits when it comes to growing more plants together. There are companion plants with specific benefits for specific plants (such as borage helping reduce hornworms for tomatos) but when you’re just starting out I think it’s easiest to focus on the companion plant multitaskers. In the second graphic I listed my favorites which I generally scatter all over my garden and plant at least 5 of them in every bed. With the exception of sunflowers (which are great companions for climbing plants or plants that need shade but may not be suitable for plants that need more sun such as tomatoes and peppers) all of them are appropriate companions for any of the vegetable guilds I listed. The main thing to note is that most of them are warm weather companion plants, in the winter cover crops such as crimson clover and winter rye should be grown between any of your cold weather vegetables and to cover any resting beds. Leaving your soil bare is always a bad idea! It’s an open invitation for weeds to take up residence and leaves your precious topsoil vulnerable to wind and water erosion.